It is the antebellum period in American history. In the South, life goes on as it has for over a century. The “unpleasantness”, as the gentry would come to call it, has not yet fouled the honeysuckled air with the smoke and ash of war.

In the North, however, the air is thick with the fallout of the industrial revolution. Everyone and everything, it seems, must either change or be changed. Society is in an almost constant state of agitation. It is here that we meet the wealthy and powerful Tyng family: Stephen, an Episcopal priest, and one of his two priest sons, Dudley.

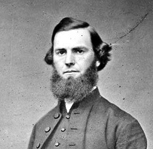

Father Stephen Tyng, rector of St. George’s in New York City, is one of the driving forces behind the emerging “low-church” movement in the Episcopal church. “Revivalism” is not yet old-time religion, it is the latest religious fad. Ministers are preaching a “social gospel”, exhorting their congregations to become more political and militant. Spiritual renewal and moral rearmament are popular sermon themes. Son Dudley is eager to carry the banner of this new reformation forward into his generation.

After graduating from seminary in Virginia, Dudley serves as priest-in-charge of several hinterland parishes before being called to the rectorship of Church of the Epiphany in Philadelphia. This parish thinks they know their new priest well: they had seen him grow-up while his father, Stephen, was their rector. Times have changed, though, and Dudley is a man of his of his time. He finds common ground with many of the dynamic and progressive young Protestant ministers in the city; but he seems unable to find common ground in his own parish.

His supporters praise him as “bold, fearless, and uncompromising” in the face of controversy. His foes condemn him as someone who just seems to seek out controversy. His style is tearing the parish apart. The vestry requests his resignation.

Some of Dudley’s parishioners leave with him and form a new parish, the Church of the Covenant. This parish will become famous in years to come as one of the “mother churches” of Reformed Episcopal Church when the Episcopal Church splits in 1874. In the meantime, Dudley and his fundamentalist clergy friends are busy planning an event billed as “A Mighty Act of God in Philadelphia”.

At this city-wide revival, Dudley achieves almost celebrity status. One evening, he preaches to a crowd of nearly 5000, and some 1000 respond to his altar-call. A few days later he retreats to his country estate for some rest and recreation.

Now, gentleman farmer Dudley has acquired the latest thing in agricultural equipment: an automated corn-shucking machine. Hands-on chap that he is, he has a go at operating it. In the process, he gets his sleeve caught in the works and his right arm is severed. A physician is summoned; but there is little he can do. Since antibiotics have not yet been discovered, infection sets in and Dudley lies dying. When asked if he has any parting words for his fans and admirers, he replies, “just tell them to stand up for Jesus”. With that, he dies.

The following Sunday, one of Dudley’s Presbyterian colleagues, Rev. George Duffield, closes his sermon with a poem he has just written, in tribute to Dudley, entitled “Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus”. The local Baptist newspaper prints it the following week. Someone then gets the idea to start singing the poem to the tune of a popular song by George Webb, “Tis Dawn, the Lark is Singing”, and rest is history.

In a chapter in the recently published diocesan history titled This Far by Faith: Tradition and Change in the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania contributor Marie Conn states that Fr. Tyng was driven from the pulpit of Philadelphia’s Episcopal Church of the Epiphany in 1856 by vestryman Pierce Butler after Tyng spoke out against slavery. At the time Butler owned more than 900 enslaved people on St. Simon’s and Butler islands in Georgia. (pp. 166,167). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for all of its association with abolition (Anthony Benezet) and the underground railroad (William Still), had a strong pro-slavery/pro-Southern stance prior to the Civil War that was evident in the city’s political and social structures.